The Belfast Blitz

Preparations in Belfast (and lack thereof)

Blackout

The outbreak of war at the start of September 1939 led to immediate changes in public life. The most noticeable of these was the blackout. Imposed on 1 September, the blackout was initiated to prevent enemy bombers from finding their targets during the hours of darkness. Homeowners had to place blackout curtains or card over windows and doors to prevent light from escaping. Where these could not be used windows were painted over with black paint.

Employers were also the subject of restrictions as blackout rules compelled factory owners to paint over skylights over factory floors. Streetlights were switched off and covers put on traffic lights and car headlights, directing their beams downwards.

The streets of Belfast and towns across the province were transformed as curb, pillars, streetlights/furniture, trees, railings, and steps were painted in white stripes to make them more visible during the blackout. But attempting to hide the country from aerial attack had its consequences.

Accident rates soared as pedestrians and motorists attempted to find their way about in the dark. Across the UK, by January 1945, the government estimated that one in five people across the UK had been injured in the blackout.

Air Raid Precautions (ARP) wardens enforced blackout regulations and ensured any exposed light was covered. Wardens called on the premises in breach of the blackout to issue warnings, but fines were also imposed.

Nevertheless, much of the population resented the blackout, as many believed that Belfast was too far away to be threatened by aerial bombardment or that there were many other more critical targets in Britain. This attitude led to a general ambivalence by the public and even politicians. Poor blackout observance was frequently reported, and the recruitment of volunteers for the ARP was poor.

Evacuation

The fear of aerial attacks on population centres caused an initial push to evacuate children to the countryside or areas less under threat. The Belfast Corporation drafted plans to evacuate 70,000 school children in Belfast in June 1939. However, there was little enthusiasm from the public as just 17,000 children were registered, and on 7 July 1940, the day appointed for transportation out of the city, little over 1,000 children turned up. Another effort was made six weeks later when 1,700 of 5,000 registered children arrived for evacuation.

As time passed and Belfast remained free of air attack, many evacuees drifted back to the city. Visitors from Britain were shocked at the prevalence of children on the streets as compared to towns and cities in Britain.

BBP21 Interviewee Alec Murray remembers:

'We were evacuated to Newtownards... we had a place to go to in Ballyalton and the lady was called Skillen, but my cousins were evacuated too... My mother was living with us and my father used to come down in order to sleep or anything, it was a big farmhouse, about six or seven of us and my cousins and the aunt with us too and my granny... It was a culture shock. I didn't like it, it was alright during the war, but you get homesick after it... Newtownards, we thought it was a million miles away. Now I can go down and it takes only ten minutes to go down the back road.'

Gas Masks

Gas masks were issued to everyone in Northern Ireland at the outbreak of war. The government expected that gas attacks would be a feature of strategic bombing of population centres, and it was recommended that people carry gas masks with them wherever they went. However, the general public soon ignored these recommendations. Children were made to carry them by their schoolteachers, who performed regular drills, but as few as one in ten adults regularly carried their gas mask.

W&M185 Interviewee Billy Montgomery shared his memory of gas masks with us:

'Yes, you had to take your gas mask every day. One day I forgot mine and I had to just, I was sent back home again, which was quite a walk back up the Old Cavehill Road, get it and then come back again. It was in a yellow metal case with a cord... a cord handle on it... there was a modification carried out on them, I remember halfway through the war, you had to go to the local ARP station and get, it was like a green filter went on the bottom of the respirator and I don't know what it was, maybe some special gas or something that they were frightened of, we never really had to wear them.'

Air Raid Shelters

The construction and provision of air raid shelters in Northern Ireland was initially slow. Early efforts saw simple shelter trenches dug in public parks. Yet by 1940, of 60,000 homes in Belfast eligible for free shelters, just 4,000 had been provided by the Belfast Corporation. The city's high-water table meant it was not very suitable for Anderson shelters, though this was a moot point as their supply was limited to areas of greater need in Britain.

Where available, Morrison shelters were provided from 1941. Named after Herbert Morrison (the Home Secretary), it was a steel shelter that could double as a table. It had detachable sides, allowing domestic use, but it could protect two adults and a child (or two small children) in a raid. It was provided in sections easily assembled in around two hours.

However, the authorities focused on erecting communal shelters. These were largely 50-person public shelters constructed in streets and thoroughfares. Made of brick and reinforced concrete, 200 were built by June 1940 and 700 by April 1941. However, this only provided shelter for a quarter of the city's population. Moreover, their design was flawed as they lacked internal supports, a failure in design that cost lives in the coming raids. The shelters also became a focus of anti-social activity, causing many to avoid them entirely and take refuge in their homes.

BBP16 Interviewee Harriet Smyth recalls:

'It was a big long shelter, must have been about a few, could have... maybe have held about near a hundred people I would think. It was a big metal shelter, a big long shelter... it was dark and damp.'

The local authorities and politicians made excuses for insufficient protection for the city's population. Some believed Belfast would never be attacked, as it was at the extreme range of German bombers. Others thought that anti-aircraft defenses in Britain would deter Germany from launching an attack. Furthermore, there was an unwarranted belief that somehow Belfast would be protected by southern Ireland's neutrality. These attitudes fed into a high degree of public and political apathy.

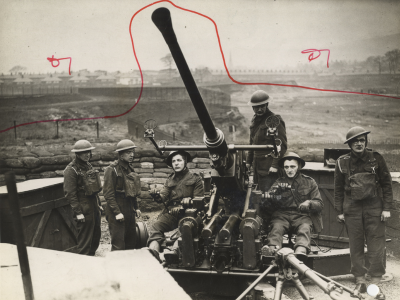

Anti-aircraft defences

Public apathy was also mirrored by lacklustre efforts by the military to protect the city. A small number of light and heavy anti-aircraft (AA) guns protected the city at the outbreak of the war, with 12 heavy 3-inch guns and eight light 40mm Bofors guns protecting the harbour estate. Thirty-two searchlights around the city supplemented the gun defences. However, the pressure of military necessity led to these being redeployed to Britain and elsewhere. When the first raid occurred on 7-8 April 1941, Belfast was protected by just 16 heavy and six light AA guns, around half of what was considered adequate for a similar-sized city in Britain.

A balloon barrage of approximately 80 sites was established over the city, with half on land and the others on barges anchored in Belfast Lough. These were hydrogen-filled balloons that hung wires that could entangle low-flying aircraft, deterring enemy dive-bombing and forcing others to fly at higher altitudes. Barrage balloons were usually flown at 1,000 to 2,000 feet, but this could be increased to 6,000 feet. A squadron of fighters was stationed at RAF Aldergrove, but they could only operate in the daytime; no night fighters were stationed in Northern Ireland.

By April 1941, no searchlight emplacements were stationed around Belfast. Two searchlight regiments had been sent to the city but were not operational by the time of the first raids. However, smokescreen generators were in place. These would be activated to obscure the industrial targets in the city, however bombs that missed their targets would inevitably fall in the densely-packed houses that surrounded the harbour estate and city centre.