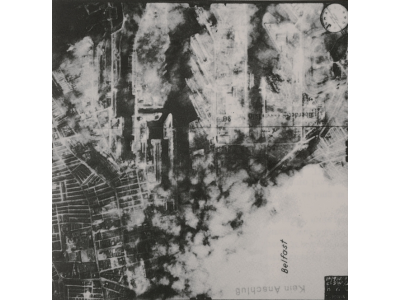

The Belfast Blitz

The Effects of the Belfast Blitz

Though Belfast was subject to relatively few attacks compared to other cities in the UK, the casualty figures were some of the worst outside London for a single raid. In total 987 people were killed in the four raids, with 710 killed in Belfast during the Easter Tuesday raid.

Though the attacks in May caused fewer casualties than in April, the raids profoundly affected the city and its industries. The Harland and Wolf shipyard ceased work for 3 days, and by September, 1,000 men were still employed in clearing sites. The engineering shops were not fully restored until early 1943.

BBP21 Interviewee Alec Murray recalls the aftermath of the blitz:

'Percy Street was an awful sight... Everybody just went down to see it, it's not like nowadays where they put a cordon round where bombs go off, everybody as just walking about and I've never saw... such devastation...'

The raids also made workers reluctant to work nightshift in shipyards, but production gradually recovered, which was at 10% of normal on 21 May 1941 and 40% by 12 June 1941. Full pre-raid output was achieved at the factory by November 1941.

Aircraft production at Short & Harland was temporarily crippled, and it was not until September 1941 before production was back to pre-raid levels. Night shift working was not restored at Short & Harland until November 1942. The raids demonstrated that concentrating production in the Harbour estate presented a tempting target for future attacks. Consequently, much of the final assembly of aircraft was dispersed to locations away from the centre of Belfast, at sites such as the King's Hall, Lisburn, Long Kesh, and Maghaberry. Despite losing much of their machinery, the Belfast ropeworks were back in full production within 3 months.

Much of the housing in the city was impacted during the attacks, with 56,000 houses destroyed or damaged, approximately half the housing stock. The damage to civilian morale was of genuine concern. There was anger at the upbeat reports from the press claiming Belfast could take it. However, such attitudes provoked resentment in areas that bore the brunt of the German attack.

The raids led to mass evacuation of the population, as tens of thousands sought to escape the city, fearful that the Luftwaffe would return. 'Ditching' became a phenomenon, where thousands of civilians abandoned the city to sleep in the surrounding countryside. Those too poor or without the benefit of relations in the countryside made nightly treks with blankets, rugs and anything that would allow them to get some semblance of sleep out in the open. Even in towns as far away as Ballymena and Enniskillen, observers noted civilians leaving towns each night despite those towns never having been bombed.

Ditching continued into the summer, though in smaller numbers. However, in the event of an alert, thousands resumed the practice. During the alert on 24 July 1941, police estimated 30,000 people vacated Belfast. This was in addition to the crash evacuation of the city of those who stayed away. Perhaps half the population left the city. In June 1941, government-ordered evacuees peaked at 70,000 but there were possible another 150,000 voluntary evacuees.