Blog

The War for Industrial Producion

Northern Ireland's unique regional politics was reflected in its experience of the Second World War. The region contributed significantly to the British war effort, especially in the production of armaments. This led to increased industrial and women's employment in the region. The workplace was modernised through occupational health, safe working hours, and trade unionism developed, whilst canteens and creches were also opened. However, the increased demand for labour in Britain led to migration for work and a moral panic about southern Irish migration to Northern Ireland. The government refused to implement industrial or military conscription in the region for fear of the political consequences. Sectarian divisions and disputes continued, total employment was not reached, and it became one of the most strike-prone areas of the UK during the Second World War. What difficulties did the region face in mobilisation for war?

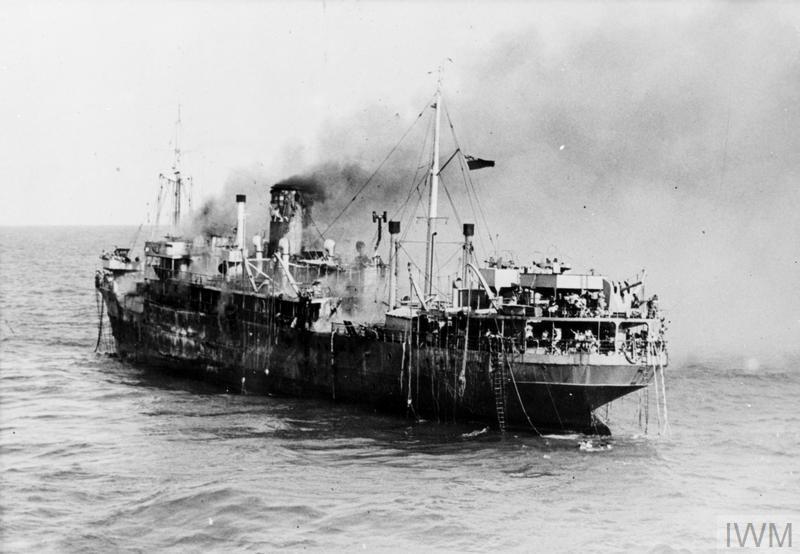

It took two years for Northern Ireland to achieve a war footing fully. The region had a devolved administration, which had to be reconciled with a UK-wide mobilisation. The Ulster Unionist Party government of the province was led by Lord Craigavon until 1940. He was replaced that year by J. M. Andrews, and finally, Sir Basil Brooke became the new Northern Ireland Prime Minister in 1943. The Northern Ireland government, however, was short-sighted in the early mobilisation for war. Both Harold MacMillan and Harold Wilson were critical of the high unemployment in the province when they visited in 1940 and 1941. Only Sir Basil Brooke, Minister for Agriculture, then Commerce, and then Prime Minister, was complimented on his dynamic leadership. This poor political leadership was compounded by inflexible local management. The region had continual industrial disputes, which became a source of contention with the British government. Probably the most critical aspect of Northern Ireland's war was its geo-strategic significance for the Battle of the Atlantic and the fight for industrial production.

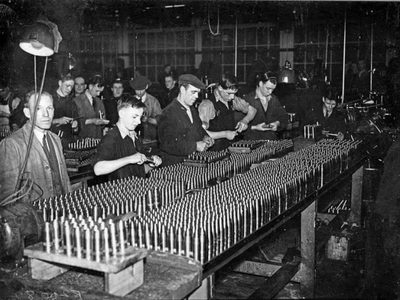

Northern Ireland contributed significantly to the war production necessary for the conflict, but the region's staple industries - linen textiles, engineering, and shipbuilding - all contracted in the 1930s. Workman and Clark, Belfast's second shipyard, was forced to close in 1935. Unemployment in 1938 stood at 30% of the industrial labour force. Once the war began, however, the linen industry was further constrained due to the use of European flax as raw material. Despite these difficulties, especially in 1940 and 1941, engineering and shipbuilding did increase production. The region produced armaments: munitions and weaponry, aircraft, tanks, ships, and small arms were all built here. Approximately 30,000 people worked at Harland and Wolff in 1942 (from a low point of 2,000 during the Great Depression). Similarly, at Short and Harland, 4,000 were employed in 1938, but by early 1942, this had risen to 12,000 employees. Mackies Foundry and Sirocco Works were both significant contributors to the war effort, whilst the local rope industry supplied Britain with a third of its ropes, cable and twines during the war. Overall, shipbuilding and engineering doubled their number of employees during the war. There was also an increase in female employment by 10,000 during the war. Alongside these industrial developments, the war also saw the increased mechanization of agriculture in the province and more female labour was deployed in agriculture.

The Second World War led to significant intervention in the workplace by the British state. In 1940, Defence Regulation Order 1305 outlawed lockouts and strikes. This legislation was expanded in 1944 to make incitement to strike also illegal. Industrial relations in Northern Ireland during the war were confrontational. The RUC recorded that 6,000 people were prosecuted during the war for participating in industrial action. There were severe confrontations between employers and employees. In Harland and Wolff, and Short and Harland, the relations between management and employees and their trade unions were strained. The trade union movement developed decisively during the war years. In 1938, Northern Ireland had 90,000 trade unionists, but by 1945, there were nearly 150,000. In the autumn of 1942, Belfast witnessed a wave of dispute, with electricians striking in September and strikes at Short and Harland in October. Churchill contacted the Northern Ireland government, stating his ‘shock’ at the industrial action. In February 1944, Belfast nearly witnessed a general strike after five shop stewards were fired from their positions in the city’s munitions industries. It only ended when the five shop stewards successfully appealed their prosecution for going on strike and a pay increase for the workers involved.

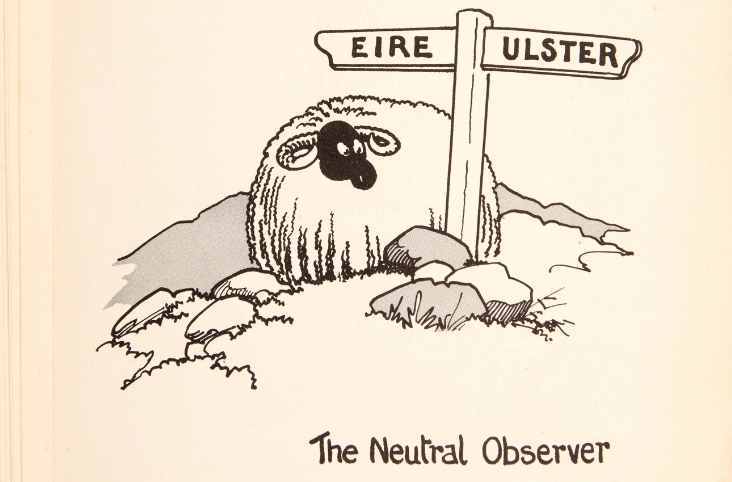

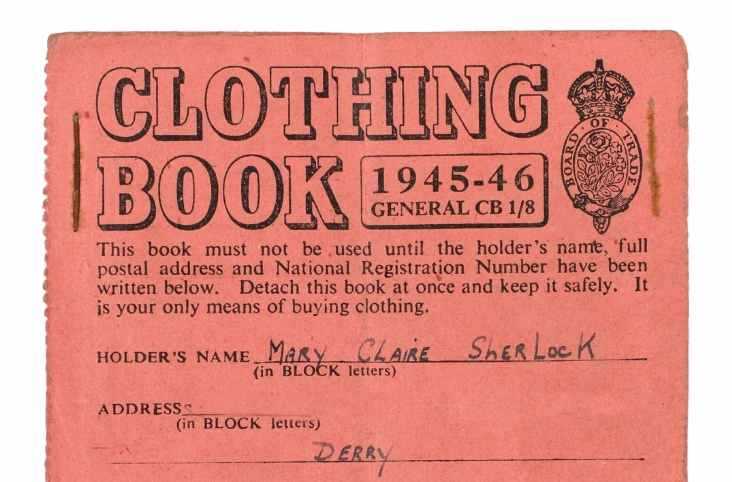

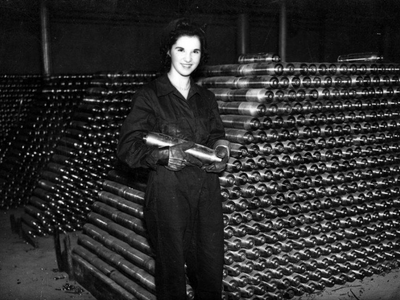

The war also offered further opportunities for women. The RUC, for example, recruited female police, although they were subject to a marriage bar. Similarly, there was employment for women in the auxiliary services for the armed forces and as additional agricultural labour. The most significant development was the type of industrial employment opened to women. This was especially important in engineering and shipbuilding. Before 1939, women were employed in manufacturing, but this was confined to the linen industry, tobacco and services. During the Second World War, women were allowed to work in traditionally male-preserved industries. This was thanks to a relaxation of craft practices in the workplace and the use of 'dilution.' 'Dilution' saw the relaxation of craft practices and radically shortened training programs. In engineering, there were 250 women employed, but by 1943, 12,500 women were employed in Northern Ireland. Yet, because of the lack of industrial or military conscription, the demand for female labour and expanded opportunities was never as significant within the province as in Britain. Despite common wartime experiences, there was continued sectarian competition for jobs within Northern Ireland. This issue was compounded by the migration of southern Irish labour to the region, referred to during the war as the 'Éire worker question.'

Northern Ireland's industrial effort demonstrated the limited experience of the conflict. The region became closer to Britain, but some felt it was only 'half in the war.' Nevertheless, hundreds of thousands of people contributed to the armed forces, civil defence, and critical war industries in the province. Female employment became more heterogeneous, as The Ulster Year Book 1947 claimed up to 20,000 women engineers had been employed in the region during the war. Politically, the war also led to an increased left-wing vote in the region, the development of public health, public housing, and education. However, the Northern Ireland government's war mobilisation, preparation, and response were poor. Sir Basil Brooke was the province's only significant political figure credited with dynamism. The war also led to political challenges, as the ruling Ulster Unionists suffered several by-election defeats. Contentious industrial relations matched this in some of the region's biggest industries. Further, the lack of industrial or military conscription meant the province never attained full employment. Similarly, whilst there was increased female employment, this was considered provisional and marriage bars continued to be used.

About the author:

Dr Christopher Loughlin is an independent labour historian. He has previously worked at Manchester University 2022-23, Newcastle University 2018-21, and obtained his training at Queen's University Belfast. His first monograph was published in 2018, Labour and the Politics of Disloyalty in Belfast, 1921-39. He has published work on labour history, loyalism, gender, and critical history theory.

Further reading:

Barton, Brian. 2015. The Belfast Blitz: The City in the War Years. Ulster Historical Foundation.

Black, Boyd. 2005. “A Triumph of Voluntarism? Industrial Relations and Strikes in Northern Ireland in World War Two.” Labour History Review (Maney Publishing) 70 (1): 5–25.

Blake, John W. 2000. Northern Ireland in the Second World War. [New ed.] Blackstaff.

Hill, Myrtle. 2003. Women in Ireland: A Century of Change. Blackstaff Press.

Ollerenshaw, Philip. 2013. Northern Ireland in the Second World War: Politics, Economic Mobilisation and Society, 1939-45. Manchester University Press.

Redmond, Jennifer. “The Largest Remaining Reserve of Manpower: Historical Myopia, Irish Women Workers and World War Two.” Saothar 36 (2011): 61–70.