BLOG

James Magennis VC

James Magennis was born on 27 October 1919 and was raised by his mother with four siblings in Majorca Street, just off Grosvenor Road, Belfast. He attended school at St Finian's, run by the De La Salle brothers, but work and money were scarce, so he followed his brother Bill into the armed forces. He initially tried to enlist in the army but was rejected; therefore, he joined the Royal Navy at the age of 15 in 1935.

Initiated into naval service at HMS Ganges, Shotley, Suffolk, nine months of training saw Magennis pass out as a First Class Boy Seaman. His first ship was the old battleship HMS Royal Sovereign, but this was short-lived, and he transferred to the cruiser HMS Enterprise. By 1938, Magennis was serving on the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes.

Called 'Mick' by his shipmates, he was promoted to Able Seaman in 1938. The naval exercises the following year were rife with rumours that war was imminent. Magennis was attending a torpedo training course when war was declared on 3 September 1939. The following month, he was drafted to his first new ship, HMS Kandahar, a K-class destroyer. Serving on the Kandahar as a quartermaster, Magennis experienced his first taste of war when HMS Kelly was torpedoed during the Norwegian campaign in May 1940. Pulling astern of the stricken vessel, the crew of the Kandahar helped recover the wounded, an event which Magennis saw firsthand, the brutality of war. He later noted, 'It was the sight of the dead and dying that struck real fear into me for the first time in my life'.

Though impacted by the sights he witnessed, Magennis showed bravery and compassion for enemy sailors when he risked his life diving into the water to drag Italian submariners to safety in June 1940. He again rescued sailors after the sinking of HMS Juno during the evacuation of Crete in May 1941.

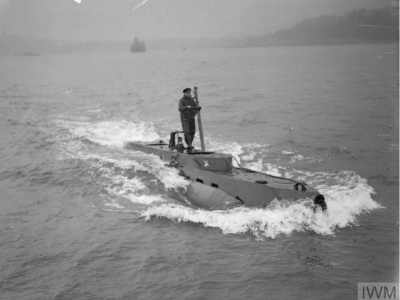

HMS Kandahar sank after hitting a mine in December 1941, forcing Magennis to swim to safety. The crew of HMS Jaguar picked him up. Magennis was assigned to the submarine service and, after training, was drafted to HMS H50 in February 1943. Magennis then volunteered for duties on X craft, a class of midget submarines built in 1943-4.

The small four-man submarines were perhaps a natural fit for Magennis, as he was 5 feet 4 inches tall, which suited him to the cramped quarters of the boats. The training was rigorous and demanding, and many candidates failed, but Magennis qualified as a diver. His first operations role was during the attack on KMS Tirpitz. Codenamed Operation Source, it was an attack by six X-craft on the 43,000-ton battleship anchored in Alten Fjord, Norway. Magennis was part of the passage crew of X-7. It was a torturous journey as the crew struggled to keep the submarine above its maximum depth of 150 feet. Magennis later described the mission as 'a hair-raising and terrifying experience'. The operational crews replaced the passage crews before the attack, which commenced on 22 September 1943.

Demolition charges exploded alongside the Tirpitz, putting the battleship out of operation until April 1944, but all the midget submarines were lost, with nine crew members killed and six captured. For his efforts during operations off Norway, Magennis was mentioned in despatches.

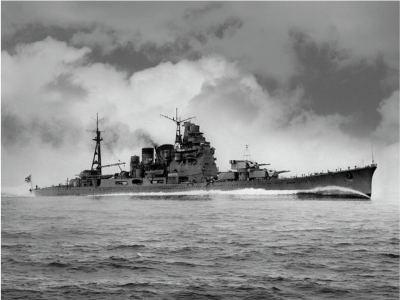

Magennis continued to train on X-craft when his unit was transferred to East-Asia, where they trained to acclimatise to operating in tropical conditions. This training culminated in the attack on the Japanese heavy cruisers Takao and Myōkō. They were anchored in the Straits of Johore off Singapore, and dominated the causeway that linked the island to the mainland.

The attack was launched on 31 July 1945. Lt. Ian Fraser was in command of XE-3, and crewed by Magennis, with Sub. Lt. William 'Kiwi' Smith, and Engine Room Artificer (equivalent to a Petty Officer) Charles Reed. The small craft was towed into position by a larger parent submarine, HMS Stygian. XE-3 slipped its tow rope from Stygian at 23:00 on 30 July and made its way west. Luck was with them as the anti-submarine netting protecting the approach was open, and they narrowly avoided detection by a Japanese sentry and a patrolling trawler. The falling tide meant the Takao's bow and stern rested on the sea bed, but Fraser positioned the submarine amidships under the cruiser's keel. Streaming with sweat, Magennis donned his diving suit and equipment and exited the submarine. Magennis' Victoria Cross (VC) citation takes up the story.

‘Leading Seaman Magennis served as Diver in His Majesty's Midget Submarine XE-3 for her attack on 31 July 1945, on a Japanese cruiser of the Atago class. The diver's hatch could not be fully opened because XE-3 was tightly jammed under the target, and Magennis had to squeeze himself through the narrow space available. He experienced great difficulty in placing his limpets on the bottom of the cruiser owing both to the foul state of the bottom and to the pronounced slope upon which the limpets would not hold. Before a limpet could be placed therefore Magennis had thoroughly to scrape the area clear of barnacles, and in order to secure the limpets he had to tie them in pairs by a line passing under the cruiser keel. This was very tiring work for a diver, and he was moreover handicapped by a steady leakage of oxygen which was ascending in bubbles to the surface. A lesser man would have been content to place a few limpets and then to return to the craft. Magennis, however, persisted until he had placed his full outfit before returning to the craft in an exhausted condition. Shortly after withdrawing Lieutenant Fraser endeavoured to jettison his limpet carriers, but one of these would not release itself and fall clear of the craft. Despite his exhaustion, his oxygen leak and the fact that there was every probability of his being sighted, Magennis at once volunteered to leave the craft and free the carrier rather than allow a less experienced diver to undertake the job. After seven minutes of nerve-racking work he succeeded in releasing the carrier. Magennis displayed very great courage and devotion to duty and complete disregard for his own safety.’

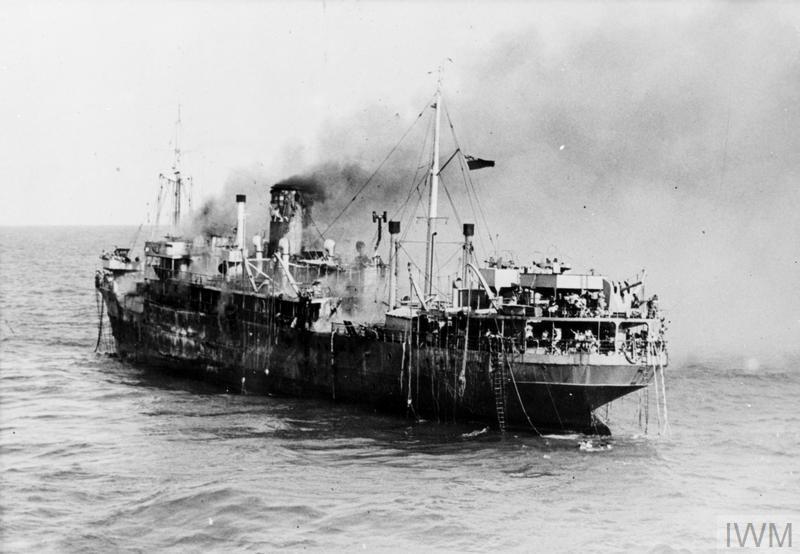

XE-1 was unable to reach the Myōkō and broke off its attack. Both craft exfiltrated the area undetected. Around 21:30, the limpet charges detonated on the hull of the Takao (the half-ton amatol charge failed to explode), tearing a massive hole in the hull. The ship settled on the sea bed, but with its main deck still above water. The two submarines rendezvoused with HMS Stygian around 4:00 on 1 August. The operation had lasted 52 hours.

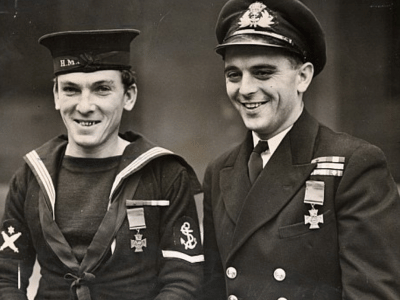

There were plans for a repeat of the mission to neutralise the Myōkō, but these were scrapped with Japan's surrender on 15 August 1945. The navy scrapped the X-craft, and Magennis was assigned to the submarine HMS Voracious. Only in November 1945 was Magennis informed by Lt. Fraser that he was to be awarded the Victoria Cross. The citation was read aloud to the assembled company of the boat, much to Magennis' embarrassment. Fraser was also awarded the VC, whereas Lt. Smith received the Distinguished Service Order, and ERA Charlie Reed the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. Life soon became one reception after another. News reached Belfast, where the press flocked to the family home in Ebor Street. Magennis was flown home and was joined by his mother, sister, and brother when he received his VC from King George VI at Buckingham Palace. Magennis’ return home prompted a street party and later a reception at Belfast City Hall, where a shilling fund was established, with donations totalling over £3000. Though touched by the sentiment and support, Magennis was embarrassed by the attention.

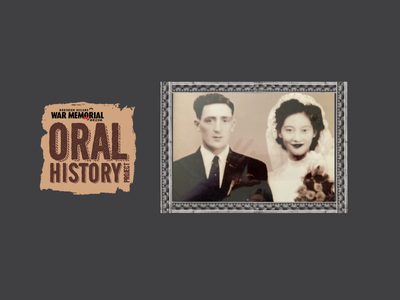

Marrying Edna Skidmore in 1946, Magennis remained in the navy until 1949 and returned to Belfast, where he was employed in RNAS Sydenham. After a family tragedy in 1951 and losing his job the following year, Magennis sold his VC to a local pawnshop for £75. Magennis explained his reason for selling his medal ‘My wife, myself, and my family were broke. You can’t eat a Victoria Cross’. The medal was returned, but the press coverage and the act caused a public furore. Increasingly, Magennis felt out of place in Belfast and moved to Rossington, near Doncaster, in February 1955, where he worked as an electrician in a coal mine.

Magennis attended reunions and receptions in honour of VC recipients, but he was clear that, post-war, all he really wanted was a quiet life. Hard times and illness dogged his later years, and he succumbed to chronic bronchitis on 12 February 1986, aged 66. Magennis was the only person from Northern Ireland to receive the VC in the Second World War. A memorial was erected in the grounds of Belfast City Hall in 1999 as a permanent tribute to Magennis’ courage.

Further reading

George Flemming, Magennis VC: The story of Northern Ireland’s only winner of the Victoria Cross (Dublin, 1998)

Richard Doherty and David Truesdale, Irish Winners of the Victoria Cross (Dublin, 2000)