Blog

The Stormont War Room

In November 2023, NIWM were approached by the O’Fee family who had two tape recordings of their father, the late Stewart Hunter O’Fee MBE (1915-2004), recorded in 2001. These tapes cover Stewart wartime memories in Belfast as well as his later political work and associations. Due to advancing technology and cassette tapes becoming obsolete they no longer had any way to listen to the tapes and wanted to digitise them to preserve the recordings for the future. With the aid of the Sound Archive at National Museums Northern Ireland, we were able to digitise these tapes and offer them back to the family as well as keep copies in the collections of NI War Memorial and National Museums NI for researchers.

Stewart was the last surviving member of the 'Stormont War Room', which met in a purpose built bunker at Stormont Castle, and who’s role was to co-ordinate civil defence measures when under enemy attack. In essence, it was a nerve centre for communications during an air raid alert, relaying messages between the various ARP posts, police stations, evacuation centres and hospitals across Belfast. Stewart and two of his colleagues in the Civil Service, Lancelot Brown and Jack Aiken, all volunteered ‘that we would be on call twenty-four hours a day, so if there was an alert we could be up there in a very short time’. Stewart lived relatively nearby in Hawthornden Drive (opposite Campbell College), close enough to cycle or even run up to Stormont Castle in the event of an air raid. Stewart was an ‘intelligence clerk’ and was the lowest rank in the room, in his own words;

‘My job was to take and to log all the messages that came in from the outposts or the city or wherever the attack was and record these in a book. There were three copies came in, we had despatch riders brought these up to Stormont Castle and I got one as Intelligence Clerk, Colonel Davies must have got the top one and Lance Brown got one to plot in a map, he plotted the places that incidents were recorded’.

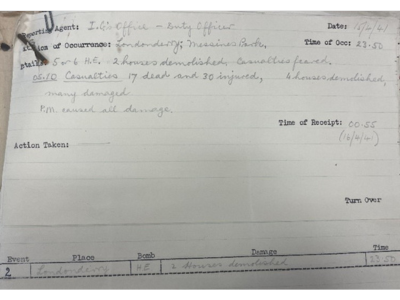

O’Fee, Brown, Aiken, and the other volunteers in the War Room were under the authority of Colonel C. S. Davies CMG DSO, who was the Senior ARP Inspector for the Ministry of Public Security. It was Colonel Davies as Operations Officer, who had to make the decision of where to send the meagre resources he had available. Essentially deciding what emergency was the priority as well as relaying all this information to Whitehall in London. This was a virtually impossible task, micro-managing emergency response while the War Room was inundated with constant messages from across the city (and further afield in the case of Londonderry, Bangor & Newtownards). Some of these situation reports and the dire news they brought survive in PRONI: MPS/1/3/2 and include these examples from 16 April 1941;

00:55am report on Messines Park, Londonderry: “5 or 6 H.E. [High Explosives] 2 Houses demolished. Casualties feared”. Followed by an update at 05:10 “Casualties 17 dead and 30 injured, 4 houses demolished, many damaged. P.M. [Parachute Mine] caused all damage”.

01:10am report from Sq. Leader Fearon, RAF at Newtownards Airfield: “H.E. & I.B’s [Incendiary Bombs] Casualties among guards”.

These situation reports all demanded immediate attention with reports of fires, explosions, unexploded bombs, roads blocked, casualties, requests for help and as well as the need for extra ambulances, wardens and pumps. For Stewart, one such report which stuck in his mind related to the May ‘Fire Raid’, the report simply stating, ‘Skipper Street ablaze from end to end”. It was Colonel Davies, along with the Minister of Public Security, Clark McDermott, who made the official request for aid from Dublin Fire Brigade. With the War Diary recording their decision;

03:23 Belfast c/c informed that fire reinforcements will be requested from Great Britain

04:00 Commissioner of Police recommends Dublin Fire Brigade be asked to assist

04:25 Home Security War Room, Whitehall asked for reinforcements from Glasgow or Liverpool

04:25 Situation Report from Belfast- Hiriam Plan recommended

04:35 Town Clerk, Dublin asked for urgent assistance from Dublin Fire Brigade.

According to the Ministry of Public Security War Room War Diary, Stewart O’Fee was on duty in the War Room for six air raid alerts on the city including ‘Dockside Raid’ (8 April 1941), ‘Easter Tuesday Raid’ (‘15/16 April 1941) & the ‘Fire Raid’ (5 May 1941) as well as three other alerts (26 April, 4 May & 24 May 1941).

While those working in the War Room escaped injury, Stewart recalls that the electricity supply was affected, stating, ‘while we were in the bunker of the so called War Room, there was a bomb landed in Stormont grounds and our bunker shook and all the lights went out for the rest of the night and we worked by candles, with candles that was our emergency source of light’. The War Diary suggested this was during the ‘Fire Raid’ on the 5th May with electric lights recorded as failing at 01:29am and only being restored at 06:15am, although the lights failed yet again on in the early hours of the 6 May alert & 7 May air raid, while O’Fee wasn’t reported as being on duty.

War Room Volunteers would often be up all night, after working their regular jobs. While they were in the relative safety of a basement bunker, their families and loved ones across the city did not have that luxury. Stewart remembers leaving on the morning after a raid, having been on duty from 12:30am until 7:03am, travelling across the city with Jack & Lancelot to check on Jack’s parents;

‘Belfast was flaming with fires, because at eight in the morning, Jack Aiken, Lancelot Brown and myself went out on our bicycles. Aiken's father and mother, I think their house had been knocked out in the first raid in the Limestone Road area I think they were and he wanted to see if they were still alive and we wanted us to ride up on our bicycles to see if we could find them. So, we rode through Belfast, all this broken glass and hydrants and so forth we negotiated that and got to where his father and mother was and discovered they were still alive’.

The Stormont War Room was officially opened for 30 different alerts, air raids or incidents between 1941-44. While, our Oral History Collection is full of accounts from civilians who suffered through the Belfast Blitz, often losing loved ones and homes; the O’Fee recordings (alongside the documents preserved in PRONI), can give us a fascinating insight into a different perspective on the Belfast Blitz. A perspective we don’t normally hear and has often been overlooked, that of the dedicated volunteers who helped coordinate efforts to aid the victims of the raids, and minimise the damage to the city.