Blog

Danger UXB: The hidden legacy of the Belfast Blitz

In August 2024, it came as quick a shock to the residents of Newtownards, Co. Down, when a relic of the past surfaced to disrupt the lives of hundreds in the small coastal town. The discovery came as workers prepared the ground for Phase III of the Rivenwood housing development on the eastern edge of the town. What may have looked like an innocuous steel cannister turned out to be a large bomb dropped during the Luftwaffe raids on Belfast on 15-16 April 1941, which became known as the Easter Tuesday Raid.

The attack devastated much of Belfast, but Derry/Londonderry, Bangor and Newtownards were also hit that night. The raiders' goal was to destroy vital industries in Belfast, but poor weather meant many German pilots missed their targets. Strategic bombing at night at this time was anything but precise; therefore, bombs and incendiaries were dropped all across Belfast and the Ards.

However, in the case of the bomb discovered at Rivenwood, which fell on what was farmland at the time, the device failed to explode. This happened to 10-20 % of all bombs dropped on the UK. Some were not meant to explode immediately. Some were fitted with time-delay fuses to disrupt rescue and recovery work after the raid had passed. Others failed to go off because they were damaged on impact, or the fuses malfunctioned due to manufacturing issues. Sabotage in the factory of origin was a real issue for the Germans. So, while some fuses, such as the ELAZ 17, could be set with an 80-hour delay, none were expected to wait over 83 years.

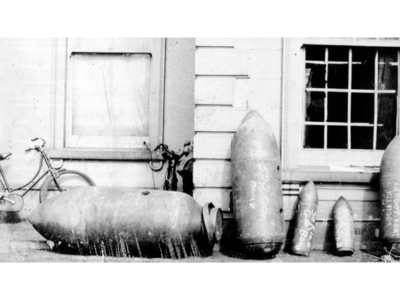

Ammunition Technical Officers identified the bomb as an SC 500, a 500 kg general-purpose bomb. They could not see either of the two fuse pockets, so they decided to ‘function’ (their term) in place after covering it in over 600 tons of sand to mitigate the effects of the blast. Very generously, they provided the Northern Ireland War Memorial Museum with a few pieces that remained, which are now on show in the gallery. However, just the other day, one of our visitors asked a pertinent question. Have there been other bombs found in the north after the war ended? In my ignorance, I had no idea. So, challenge accepted. I checked the newspaper archives, and lo and behold, there were more than I imagined.

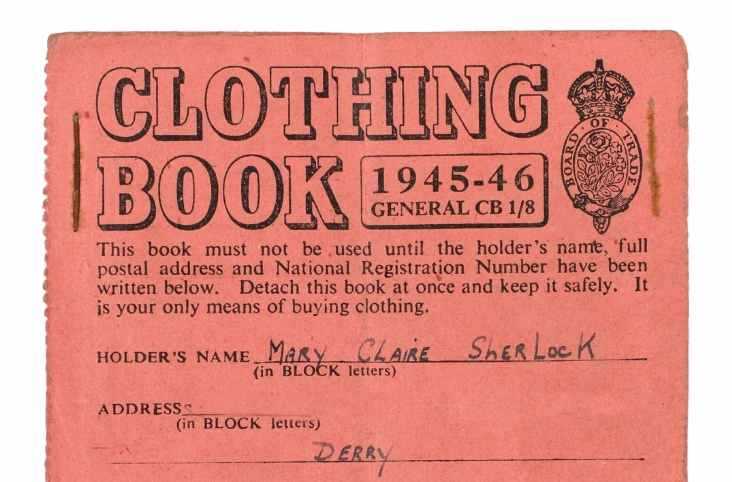

As expected, the vast majority of unexploded bombs were discovered soon after the raids and continued to be found during the war years. When peace came in August 1945, the people of Northern Ireland attempted to get on with life as usual, albeit with some lasting irritants of wartime, such as rationing, which continued until 1954. Yet the guns had not long fallen silent when, at the start of 1946, a bomb was discovered at Cable Street off the Newtownards Road, Belfast.

The Belfast Newsletter reported on 17 January that Royal Engineers had excavated a 20-foot deep shaft to reach the bomb. They worked on the device for two weeks before the two fuses of the SC 500 were deactivated. However, they could only temporarily neutralise the second fuse using a device known as a 'clock stopper', a powerful electromagnet which could halt the fuse mechanism when powered up. The engineers then steamed out the explosive filler. The still dangerous bomb was then removed by the army to open ground at Lisnabreeny, Castlereagh, and destroyed. Interestingly, the residents were only evacuated for the final two days of the operation. Captain John Deacon, 27th Bomb Disposal Company, led the operation, and it was noted that this was his 374th bomb defusal. Worryingly, the Newsletter report ended 'It is understood that there are still two unexploded bombs in the Ballymacarrett area' though it gave no further details.

Another bomb was discovered at Sydenham airport the following month, this time an SC 250, lying just '30 yards away from the aircraft factory'. Captain Deacon was unwell, so Captain H.C. Ruth was sent from England, where a novel means of using concrete piping instead of timber supports allowed the completion of the operation in just four days.

Captain Deacon and his team were again in action in March 1946, when they were called out to deal with an SC 250 buried 15 feet in a field at Six-Road-Ends, Ballygrainey, Co. Down. The nature of the soil, flooding and the position of the fuses under the bomb meant the army detonated the bomb in place. German prisoners of war assisted in the operation, employed in digging at the site to uncover the device. Captain Deacon added that another five or six bombs had been reported and were awaiting disposal.

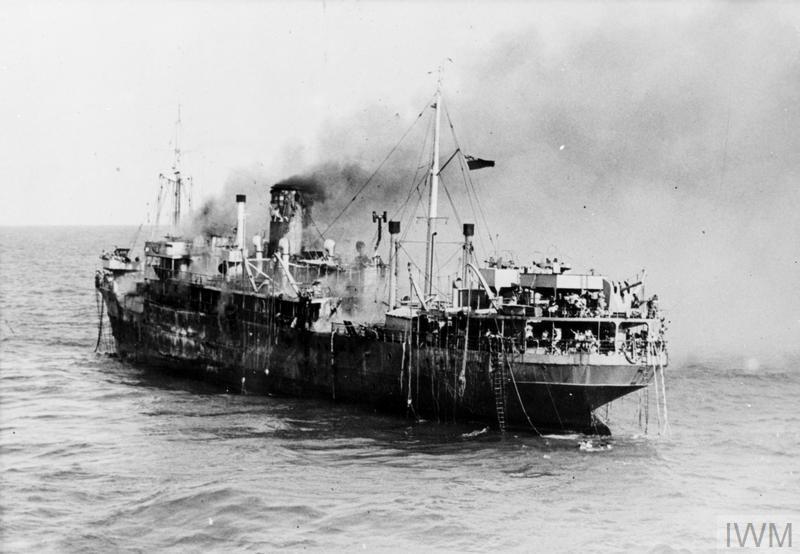

Deacon and his men seemed to catch a break as the subsequent report was not until July 1952, when a dredger in Belfast harbour lifted a bomb from the silt and deposited it on board. Captain Deacon and his men appear to be absent, as a specialist from England was dispatched to deal with it. A similar incident occurred in September the following year, when the anchor of a cargo vessel hooked a 50 kg bomb. After snagging the bomb, the ship steamed to its berth. Bomb specialists Col. Wilson and Capt. Webb declared it 'probably still live' before taking it away in a car to Thiepval Barracks, Lisburn, for later disposal.

By far the greatest number of unexploded German bombs were uncovered in the watery and muddy confines of Belfast Lough. When work commenced to dredge the channel in 1959, contractors got a lot more than they bargained for. An Army bomb disposal unit was called to Belfast harbour on 23 January 1959 to deal with an SC 250 dredged from the bottom of Belfast Lough. As the military prepared to transport the device ashore, the ATOs received news of a second bomb. The discovery prompted a strike by workmen claiming they had been refused an extra £5 ‘danger money' by their employers, but this was soon resolved. The bombs were brought to Ballykinlar for disposal, but within two weeks, the bomb disposal team was back at the docks.

Two more bombs were dredged from Herdman Channel on 5 February. By 6 February, the number of bombs discovered had increased to five, causing the closure of the port as the bombs were brought to reclaimed ground on the foreshore for controlled detonation. Navy experts arrived to support the army, as the numbers continued to rise and by 7 February, 12 bombs had been discovered, all reported weighing 100 pounds (likely SC-50s). All the bombs were removed for disposal by the army.

Mrs Rebeka Hyde of Lanark Street, Belfast, got the shock of her life in May 1962 when she decided to tidy up a bedroom for her visiting sister. Rummaging through the jumble, she put her hand on it. A former munitions factory worker, she knew it was something dangerous and phoned the police. Army bomb disposal experts considered the device relatively stable but still took it away for safe disposal.

On 9 May 1967, reports surfaced of a bomb found near the new motorway construction off the Broughshane Road, Crebilly. Locals knew there was a bomb dropped in the area, as they had seen a German aircraft (rather lost it would seem) drop a bomb roughly a mile north of St Patrick's Barracks, Ballymena. Army experts positively identified the device, but they assured the local farmers that it was the only one and no others had been detected.

Sometimes what was considered innocent turned out to be anything but. On 27 August 1967, a crane driver working on the M2 at the foreshore near Duncrue Road picked up what looked like a bomb in the bucket of his excavator. However, army experts assured the driver that it was, in fact, a target indicator used to identify targets for practice bomb runs and was perfectly safe. It was loaded on a trailer and taken to reclaimed ground to be destroyed. However, the experts were mistaken.

The next day, a 'controlled' detonation resulted in a massive blast that smashed hundreds of windows, knocked passers-by to the ground, and sent a pall of smoke 500 feet into the air. It was not a target indicator but an unexploded 500 kg bomb. A civilian foreman was wounded in the hand by shrapnel, but he considered this a lucky escape. Windows at the nearby Mount Vernon flats were shattered. The officer in charge, Capt. Brown said he had never come across a bomb with an aluminium case before. This suggests that he had never seen a German parachute mine/sea mine. Both the Luftmine A (500Kg) and Luftmine B (1,000 KG) had aluminium cases. The day after the explosion, a specialist team was sent to conduct a complete bomb survey to ensure no more unwelcome surprises were lurking along the foreshore. Army teams used sophisticated mine locators, but after two weeks, the area along the route of the M2 was declared clear.

As the Troubles took hold in Belfast, the discovery of a Second World War bomb was reported almost as a refreshing interlude by the Belfast Telegraph on 6 August 1970. But it was not something dropped during the Blitz, but a 17-pound shell, likely a relic from the First World War, brought home as a trophy. After this, we hear nothing more until the appearance of the Rivenwood bomb in 2024. One of the most frequent questions that came up after this incident was, 'Are there any more?' It is impossible to say if there are any more relics from the German raids waiting to be discovered. All we can hope is that this was the last of them.

About the Author:

Dr James O'Neill is a historian and the Collections Officer here at the Northern Ireland War Memorial.