Blog

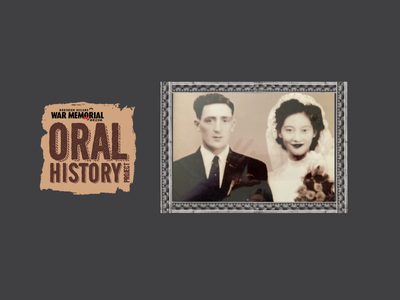

Ike's Big Rig

Throughout his life, Dwight D. Eisenhower made four visits to Northern Ireland. From those, the first in 1942 has been largely forgotten, while the second in 1944 has become the most celebrated and commemorated. In August 1945 rapturous crowds greeted him in Belfast, while in 1962 his last visit was only a single-day stopover. Locally, Eisenhower's appeal and the weight his association can carry has led to some tenuous historical connections. Yet one genuine and tangible link has remained relatively forgotten: originating at Langford Lodge on the shores of Lough Neagh.

Known as the 3rd Base Air Depot and Army Air Force Station 597, Langford Lodge was one of the largest sites associated with the American presence in Northern Ireland during the Second World War. Operated by the Lockheed Overseas Corporation (LOC) and the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), at its peak over 6000 personnel worked on the airfield with the main activities including aircraft preparation, servicing, repair and modifications. To achieve this, the site had a broad range of manufacturing facilities and was well-equipped to take a project from initial design through to final production assembly; the Lockheed P-38 Droop Snoot being a notable example. Yet possibly their most prestigious assignment didn’t involve any aircraft at all and began in early 1944, when the LOC was contacted by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) and tasked with designing and constructing mobile headquarters and accommodation trailers. To be used by none other than General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

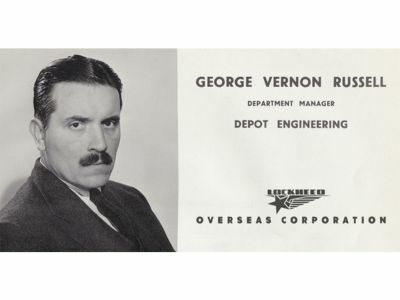

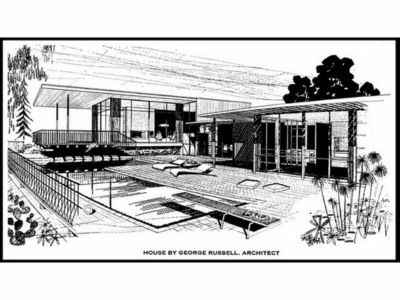

The mastermind who led the project was LOC’s George Vernon Russell, whose design credentials and capabilities were undisputed. He attended the California Institute of Technology for a year before studying architecture at the University of Washington in Seattle. After graduating in 1928, he left for France, attending a summer course at the school of architecture in Fontainebleau, then travelling throughout Europe. Returning to the United States, Russell began his career as a draughtsman in New York City, then collaborated with Douglas Honnold, designing houses for some of Hollywood’s elite. In 1937, Russell co-designed the Hollywood Reporter Building on Sunset Boulevard. However, although his Californian home was renowned for its connection to the film industry, it was an altogether different type of business that would soon change the course of his life.

The Lockheed Aircraft Company was founded in Hollywood in 1926 and moved to Burbank Airport in 1928. After America joined the war, Russell became involved with their LOC subsidiary and, by June 1942, had arrived in Northern Ireland, where, far from his Californian projects, Russell’s abilities were employed in the muddy fields of County Antrim. Appointed as the Department Manager Depot Engineering, and while construction at Langford Lodge was still in its infancy, Russell carried out a survey, recommending adjustments to the plans for production requirements. He oversaw a diverse range of work on the base, mainly focusing on its facilities, with his department developing specialist sections specifically for buildings, structural engineering, architecture, utilities, and electrical systems. By 1944, Russell’s department had completed projects at Langford that ranged from laying hardstandings to installing toilets and erecting hangars. Further afield, they carried out surveys at Greencastle and Maghaberry and oversaw the installation of synthetic training devices.

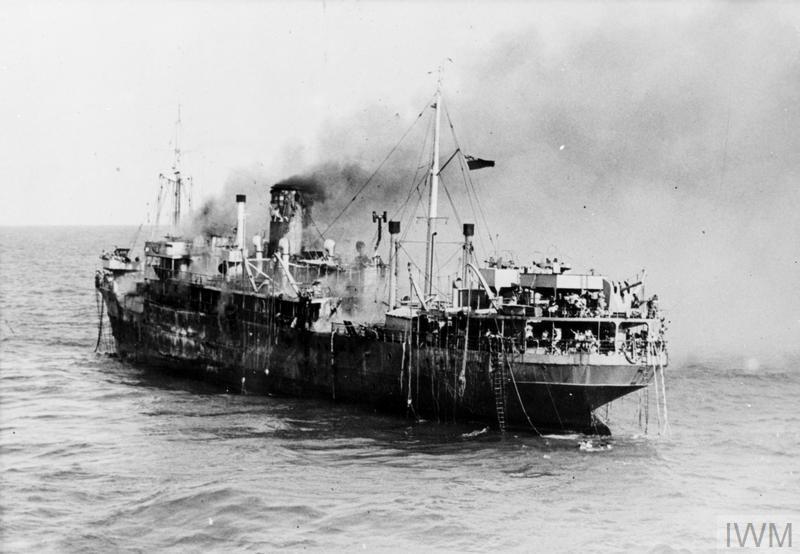

Before the end of 1942, LOC’s technicians at Langford Lodge had proven they were clearly adept at delivering niche or unusual design projects. Over a year before SHAEF’s requirement arrived, they gained experience in fitting out semi-trailers by designing and building a workshop on wheels for the USAAF, known as a Mobile Repair Unit (MRU). That concept consisted of a tractor unit (commonly an Autocar U-7144T or Federal 94x43) towing two semi-trailers joined by a dolly. Externally, the trailers were comparable to the civilian Fruehauf Warehousemen’s Van, and the adapted design included one fitted as a workshop and another as accommodation. The units were intended to carry a team of specialists and equipment to the site of an aircraft’s emergency landing and effect the necessary repairs, enabling it to depart. Four MRUs had been completed at Langford by December 1942, and by July 1943, 21 were operating in the field. Initially manned by a combination of LOC and military personnel, LOC’s contribution was phased out as the military became more proficient. Under LOC supervision, a total of 512 aircraft were returned to service using the units.

At a glance, Eisenhower's trailers looked somewhat similar to the MRU. However, the main body was based on an existing Keystone 8-Ton Instrument Shop semi-trailer used by the USAAF for the repair, calibration and maintenance of aircraft instruments. Measuring 28 feet in length, one trailer was fitted out as an operations room, with a conference table, maps wound on recessed rollers and a projection screen. With the exterior retaining a stock military look, Russell was responsible for the design of the interior, which, although utilitarian in design, was clearly above normal army specifications: described as a study in glistening chrome, highly polished black linoleum floors, delicately tinted pearl grey walls and ceilings and green leather upholstered furniture. Additionally, a smaller caravan was converted from a mobile photo laboratory into living quarters. All the trailers were built using existing stock and parts held at Langford Lodge, and the initial units were completed in 60 days. As the first trailers were ready for deployment, Russell’s involvement came to the attention of the media and was widely reported in American newspapers. Some of them describe his creation as the ‘Shaef-mobile.’

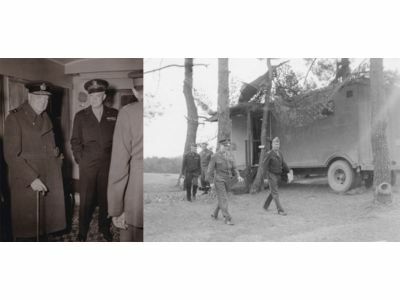

As preparations for D-Day accelerated, SHAEF split its headquarters operations between two sites: SHAEF Main at Bushy Park and SHAEF Forward near Southwick House, just north of Portsmouth. Code-named SHARPENER, it was here that the trailers were first employed, hidden under trees and camouflaged netting. Unusually, the lengthiest account describing them appears in Cornelius Ryan’s 1959 book The Longest Day. In it, Eisenhower was described trying to relax in his sparsely furnished trailer, which Ryan noted the General had now christened his ‘Circus Wagon.’

‘Eisenhower's trailer, a long, low caravan somewhat resembling a moving van, had three small compartments serving as bedroom, living room and study. Besides these, neatly fitted into the trailer's length was a tiny galley, a miniature switchboard, a chemical toilet and, at one end, a glass-enclosed observation deck. But the Supreme Commander was rarely around long enough to make full use of the trailer. He hardly ever used the living room or the study; when staff conferences were called he generally held them in a tent next to the trailer. Only his bedroom had a "lived-in" look. It was definitely his: There was a large pile of Western paperbacks on the table near his bunk, and here, too, were the only pictures -- photographs of his wife, Mamie, and his twenty-one-year-old son, John, in the uniform of a West Point cadet. From this trailer Eisenhower commanded almost three million Allied troops.’

The trailers remained at the SHARPENER camp for two months. However, SHAEF would soon be on the move with one contemporary account saying, ‘When General Eisenhower moved his headquarters from Britain to France to maintain the closest possible contact with his rapidly advancing armies, he took with him a three-unit trailer caravan which was designed and built at the Lockheed Overseas Corporation base in Northern Ireland.’

The trailers were deployed in a camp code-named SHELLBURST and situated near Tournières, France. Established on 7 August, this new SHAEF Forward was where Eisenhower welcomed Prime Minister Winston Churchill, General Charles De Gaulle and a string of senior military figures. The trailers remained there until September, after which SHAEF Forward moved to Reims, then to Versailles. By the middle of February 1945, SHAEF Forward had moved indoors at the Collège Moderne et Technique de Reim, where the first act of surrender of Nazi Germany was signed on 7 May 1945.

One example did survive the post-war period. After returning to the United States in 1955, it was acquired by the US Army Quartermaster Museum, where it was stored. It was fully restored and, in 2001, placed on permanent public display inside the museum.

As for Russell, after the LOC contract ended and a year after the trailers were deployed to France, Russell returned to California and the world of architecture. Factories and a hospital were among his first projects. Russell joined the American Institute of Architects (AIA), Southern California Chapter, in 1947, and became its director from 1955 to 1958. He later designed buildings for the Lockheed Aircraft Service Inc. at Ontario International Airport.

George Vernon Russell died aged 83 at his Pasadena home on 17 March 1989. While the numerous buildings he designed are a testament to his design capabilities, when Russell left Northern Ireland and returned to the US, he took with him the plans for Eisenhower's trailers. If anything, it's indicative of the pride he had in that particular project and its small contribution to the war effort.

About the author:

Clive Moore is the author of NIWM publication, The American Red Cross in Northern Ireland during the Second World War, and runs the US Forces in Northern Ireland during WW2 Flickr page.

With thanks to:

- Colin Russell

- The US Army Quartermaster Museum

- Sources: National Archives and Records Administration and Air Force Historical Research Agency